Paddy Compass Namadbara: for the first time, we can name an artist who created bark paintings in Arnhem Land in the 1910s

The bark painting depicting a barramundi that Namadbara created for Spencer at Oenpelli in 1912 and that he identified in the interview with Lance Bennett in 1967, now in Museums Victoria Spencer/Cahill Collection (object X 19909).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

For students of Australian art and art collectors around the globe, Arnhem Land is synonymous with bark painting: sheets of tree bark carefully prepared as a canvas for painting by Aboriginal artists.

Bark painters such as John Mawurndjul and Yirawala are some of the most internationally renowned and sought-after Australian artists.

As the market for bark paintings emerged in the early 20th century, recording the name of individual artists was far from the collector’s mind. Museums and art galleries are full of early artworks, sometimes attributed to particular “clans” or geographic areas, but rarely including the name of the artists.

Such collections are routinely named after the collector rather than the creators. One such collection, the Spencer/Cahill Collection at Museums Victoria, is the focus for our ongoing research project.

The Spencer/Cahill Collection is vast and includes many precious objects collected by Sir Baldwin Spencer when he visited Oenpelli (Gunbalanya), Northern Territory in 1912. He later acquired further artworks and objects via his “on the ground” contact, buffalo shooter Paddy Cahill.

The Oenpelli settlement with Arrkuluk Hill in the background, c. 1912–14, photograph by Mervyn Holmes or Elsie Masson. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1998.306.120

Our project’s main focus is the approximately 170 bark paintings commissioned at Oenpelli between 1912 and 1922.

Earlier bark paintings in museum collections were generally removed from bark huts found by explorers and collectors during their travels. Spencer and Cahill took the additional step of commissioning paintings on bark from the artists: these works represent the birth of the bark painting Aboriginal art movement.

Spencer’s earlier collecting experiences had been conducted to document – as Spencer and others described – a “doomed race” before it became extinct.

In Oenpelli, Spencer was mesmerised by local artists who decorated their stringy bark huts with paintings depicting animals and spirit beings, which resemble paintings found in rock shelters in the vicinity.

He compared the delicate lines in the artworks with “civilised” Japanese or Chinese artworks and concluded the local bark paintings were:

so realistic, always expressing admirably the characteristic features of the animal drawn, that anyone acquainted with the original can identify the drawings at once.

Spencer’s encounter led him to refigure his perception of Aboriginal art towards a more aesthetic appreciation. At Oenpelli, he selected a handful of the most skilful artists to paint a series of bark paintings for him.

He left with 50 artworks. Over the following years, around another 120 barks were sent down to Melbourne.

Spencer did not record the name of the artist for each painting. But, thanks to an unpublished interview from 1967, we can now successfully link bark paintings from this collection to an individual artist.

Paddy Compass Namadbara

Paddy Compass Namadbara on Minjilang (Croker Island) in 1967, photographed by Lance Bennett. The young girl is Namadbara’s granddaughter Elaine, daughter to his adopted son Thompson Yulidjirri. Estate of Lance Bennett, courtesy of Barbara Spencer

Paddy Compass Namadbara (c. 1892-1978) is remembered by people in western Arnhem Land as a skilful artist, a “clever man”, a strong community leader and family man.

During the 1950s and 1960s he spent much of his time on Minjilang (Croker Island), where he often painted alongside contemporary artists such as Yirawala and Jimmy Midjaumidjau.

In 1967 he was visited by researcher Lance Bennett, who was there to collect bark paintings and information for a book he was writing on contemporary Aboriginal art.

During these interviews, Namadbara casually identified his own works in a book published by Baldwin Spencer in 1914, Native tribes of the Northern Territory of Australia. One work features a barramundi, another a swamp hen, black bream and painted hand stencils.

The painting Namadbara created in 1912 depicting a swamp hen, black bream and his decorated hand stencils, now in Museums Victoria (object X 19887).

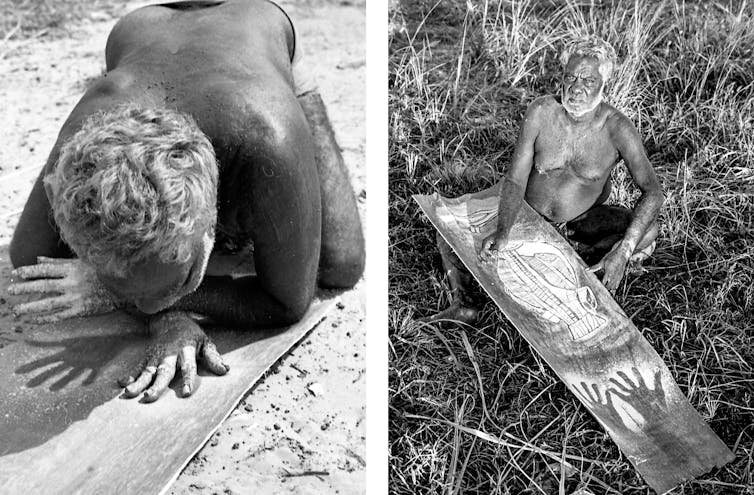

Bennett asked Namadbara to recreate this painting from 1912, a painting now in The Bennett Collection at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

The same motifs painted in 1967 for Lance Bennett, now part of the Bennett Collection in the National Museum of Australia (object 1985.0246.0109).

Bennett took the time to ask Namadbara about his personal experiences of Spencer’s visit to Oenpelli in 1912. Namadbara said Spencer asked chosen artists to create bark paintings on small, transport-friendly bark sheets, which they had never done before. This transformed the traditional bark-hut paintings into a new media: bark paintings.

Cahill, who acted as a middleman, is remembered by Namadbara as asking Aboriginal people to shed their western clothing so Spencer could film and photograph ceremonies that were “properly old fashioned”.

Paddy Compass Namadbara recreating the 1912 bark painting on Minjilang (Croker Island) in 1967, photographed by Lance Bennett. Estate of Lance Bennett, courtesy of Barbara Spencer

Spencer asked Namadbara to cross his hands when he created his hand stencils on the bark with the swamp hen and the black bream, which the artist found peculiar. They asked the artists to leave some of the paintings not fully decorated, so that the motifs would stand out better in photographs.

The payment for the 50 bark paintings consisted of a bag of tobacco and two bags of flour.

Ongoing connection

The master artists who created works for early collectors deserve to be recognised, as do the vital ongoing connections that remain between the paintings and the communities from which they were acquired.

Gabriel Maralngurra, Namadbara’s kin-grandson and one of the researchers on this project, explains:

these paintings they remain part of us, part of our community. It doesn’t matter if they are far away, we still hold them close.

Being able to identify the artists in this and other museum collections revitalises the significance of these artworks for contemporary First Nation communities, artists and their families.

It also assists cultural institutions to better understand the significance and ongoing cultural links to these collections – collaboratively charting a path for this priceless Australian heritage.

Joakim Goldhahn, Rock Art Australia Ian Potter Kimberley Chair, The University of Western Australia; Gabriel Maralngurra, Co-manager, Injalak Arts, Indigenous Knowledge; Luke Taylor, Adjunct Fellow, Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit, Griffith University, Australian National University; Paul S.C.Taçon, Chair in Rock Art Research and Director of the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU), Griffith University, and Sally K. May, Associate Professor, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.